Comic strip for 2026/03/01

We coined a new term on the Oxide and Friends podcast last month (primary credit to Adam Leventhal) covering the sense of psychological ennui leading into existential dread that many software developers are feeling thanks to the encroachment of generative AI into their field of work.

We're calling it Deep Blue.

You can listen to it being coined in real time from 47:15 in the episode. I've included a transcript below.

Deep Blue is a very real issue.

Becoming a professional software engineer is hard. Getting good enough for people to pay you money to write software takes years of dedicated work. The rewards are significant: this is a well compensated career which opens up a lot of great opportunities.

It's also a career that's mostly free from gatekeepers and expensive prerequisites. You don't need an expensive degree or accreditation. A laptop, an internet connection and a lot of time and curiosity is enough to get you started.

And it rewards the nerds! Spending your teenage years tinkering with computers turned out to be a very smart investment in your future.

The idea that this could all be stripped away by a chatbot is deeply upsetting.

I've seen signs of Deep Blue in most of the online communities I spend time in. I've even faced accusations from my peers that I am actively harming their future careers through my work helping people understand how well AI-assisted programming can work.

I think this is an issue which is causing genuine mental anguish for a lot of people in our community. Giving it a name makes it easier for us to have conversations about it.

My experiences of Deep Blue

I distinctly remember my first experience of Deep Blue. For me it was triggered by ChatGPT Code Interpreter back in early 2023.

My primary project is Datasette, an ecosystem of open source tools for telling stories with data. I had dedicated myself to the challenge of helping people (initially focusing on journalists) clean up, analyze and find meaning in data, in all sorts of shapes and sizes.

I expected I would need to build a lot of software for this! It felt like a challenge that could keep me happily engaged for many years to come.

Then I tried uploading a CSV file of San Francisco Police Department Incident Reports - hundreds of thousands of rows - to ChatGPT Code Interpreter and... it did every piece of data cleanup and analysis I had on my napkin roadmap for the next few years with a couple of prompts.

It even converted the data into a neatly normalized SQLite database and let me download the result!

I remember having two competing thoughts in parallel.

On the one hand, as somebody who wants journalists to be able to do more with data, this felt like a huge breakthrough. Imagine giving every journalist in the world an on-demand analyst who could help them tackle any data question they could think of!

But on the other hand... what was I even for? My confidence in the value of my own projects took a painful hit. Was the path I'd chosen for myself suddenly a dead end?

I've had some further pangs of Deep Blue just in the past few weeks, thanks to the Claude Opus 4.5/4.6 and GPT-5.2/5.3 coding agent effect. As many other people are also observing, the latest generation of coding agents, given the right prompts, really can churn away for a few minutes to several hours and produce working, documented and fully tested software that exactly matches the criteria they were given.

"The code they write isn't any good" doesn't really cut it any more.

A lightly edited transcript

Bryan: I think that we're going to see a real problem with AI induced ennui where software engineers in particular get listless because the AI can do anything. Simon, what do you think about that?

Simon: Definitely. Anyone who's paying close attention to coding agents is feeling some of that already. There's an extent where you sort of get over it when you realize that you're still useful, even though your ability to memorize the syntax of program languages is completely irrelevant now.

Something I see a lot of is people out there who are having existential crises and are very, very unhappy because they're like, "I dedicated my career to learning this thing and now it just does it. What am I even for?". I will very happily try and convince those people that they are for a whole bunch of things and that none of that experience they've accumulated has gone to waste, but psychologically it's a difficult time for software engineers.

[...]

Bryan: Okay, so I'm going to predict that we name that. Whatever that is, we have a name for that kind of feeling and that kind of, whether you want to call it a blueness or a loss of purpose, and that we're kind of trying to address it collectively in a directed way.

Adam: Okay, this is your big moment. Pick the name. If you call your shot from here, this is you pointing to the stands. You know, I – Like deep blue, you know.

Bryan: Yeah, deep blue. I like that. I like deep blue. Deep blue. Oh, did you walk me into that, you bastard? You just blew out the candles on my birthday cake.

It wasn't my big moment at all. That was your big moment. No, that is, Adam, that is very good. That is deep blue.

Simon: All of the chess players and the Go players went through this a decade ago and they have come out stronger.

Turns out it was more than a decade ago: Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov in 1997.

Tags: definitions, careers, ai, generative-ai, llms, ai-assisted-programming, oxide, bryan-cantrill, ai-ethics, coding-agents

That’s right — this little device is what stood between me and the ability to run an even older piece of software that I recently unearthed during an expedition of software archaeology.

For a bit more background, I was recently involved in helping a friend’s accounting firm to move away from using an extremely legacy software package that they had locked themselves into using for the last four decades.

This software was built using a programming language called RPG (“Report Program Generator”), which is older than COBOL (!), and was used with IBM’s midrange computers such as the System/3, System/32, and all the way up to the AS/400. Apparently, RPG was subsequently ported to MS-DOS, so that the same software tools built with RPG could run on personal computers, which is how we ended up here.

This accounting firm was actually using a Windows 98 computer (yep, in 2026), and running the RPG software inside a DOS console window. And it turned out that, in order to run this software, it requires a special hardware copy-protection dongle to be attached to the computer’s parallel port! This was a relatively common practice in those days, particularly with “enterprise” software vendors who wanted to protect their very important™ software from unauthorized use.

Sadly, most of the text and markings on the dongle’s label has been worn or scratched off, but we can make out several clues:

- The words “Stamford, CT”, and what’s very likely the logo of a company called “Software Security Inc”. The only evidence for the existence of this company is this record of them exhibiting their wares at SIGGRAPH conferences in the early 1990s, as well as several patents issued to them, relating to software protection.

- A word that seems to say “RUNTIME”, which will become clear in a bit.

My first course of action was to take a disk image of the Windows 98 PC that was running this software, and get it running in an emulator, so that we could see what the software actually does, and perhaps export the data from this software into a more modern format, to be used with modern accounting tools. But of course all of this requires the hardware dongle; none of the accounting tools seem to work without it plugged in.

Before doing anything, I looked through the disk image for any additional interesting clues, and found plenty of fascinating (and archaeologically significant?) stuff:

- We’ve got a compiler for the RPG II language (excellent!), made by a company called Software West Inc.

- Even better, there are two versions of the RPG II compiler, released on various dates in the 1990s by Software West.

- We’ve got the complete source code of the accounting software, written in RPG. It looks like the full accounting package consists of numerous RPG modules, with a gnarly combination of DOS batch files for orchestrating them, all set up as a “menu” system for the user to navigate using number combinations. Clearly the author of this accounting system was originally an IBM mainframe programmer, and insisted on bringing those skills over to DOS, with mixed results.

I began by playing around with the RPG compiler in isolation, and I learned very quickly that it’s the RPG compiler itself that requires the hardware dongle, and then the compiler automatically injects the same copy-protection logic into any executables it generates. This explains the text that seems to say “RUNTIME” on the dongle.

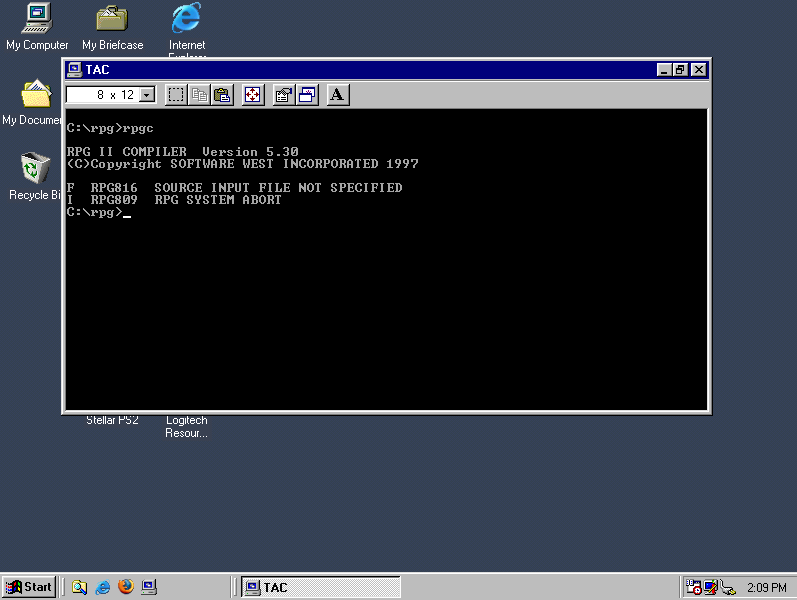

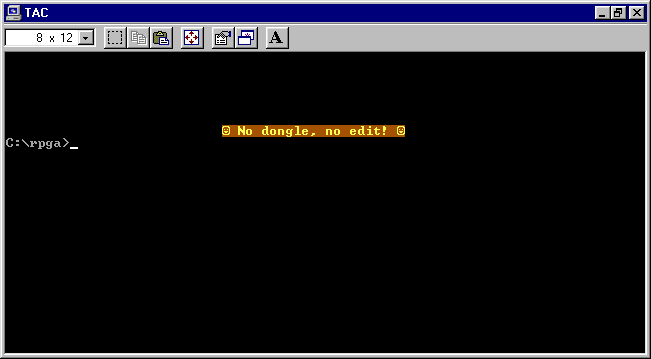

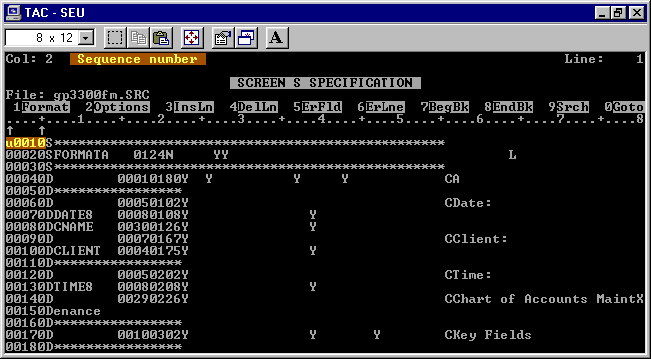

The compiler consists of a few executable files, notably RPGC.EXE, which is the compiler, and SEU.EXE, which is a source editor (“Source Entry Utility”). Here’s what we get when we launch SEU without the dongle, after a couple of seconds:

A bit rude, but this gives us an important clue: this program must be trying to communicate over the parallel port over the course of a few seconds (which could give us an opportunity to pause it for debugging, and see what it’s doing during that time), and then exits with a message (which we can now find in a disassembly of the program, and trace how it gets there).

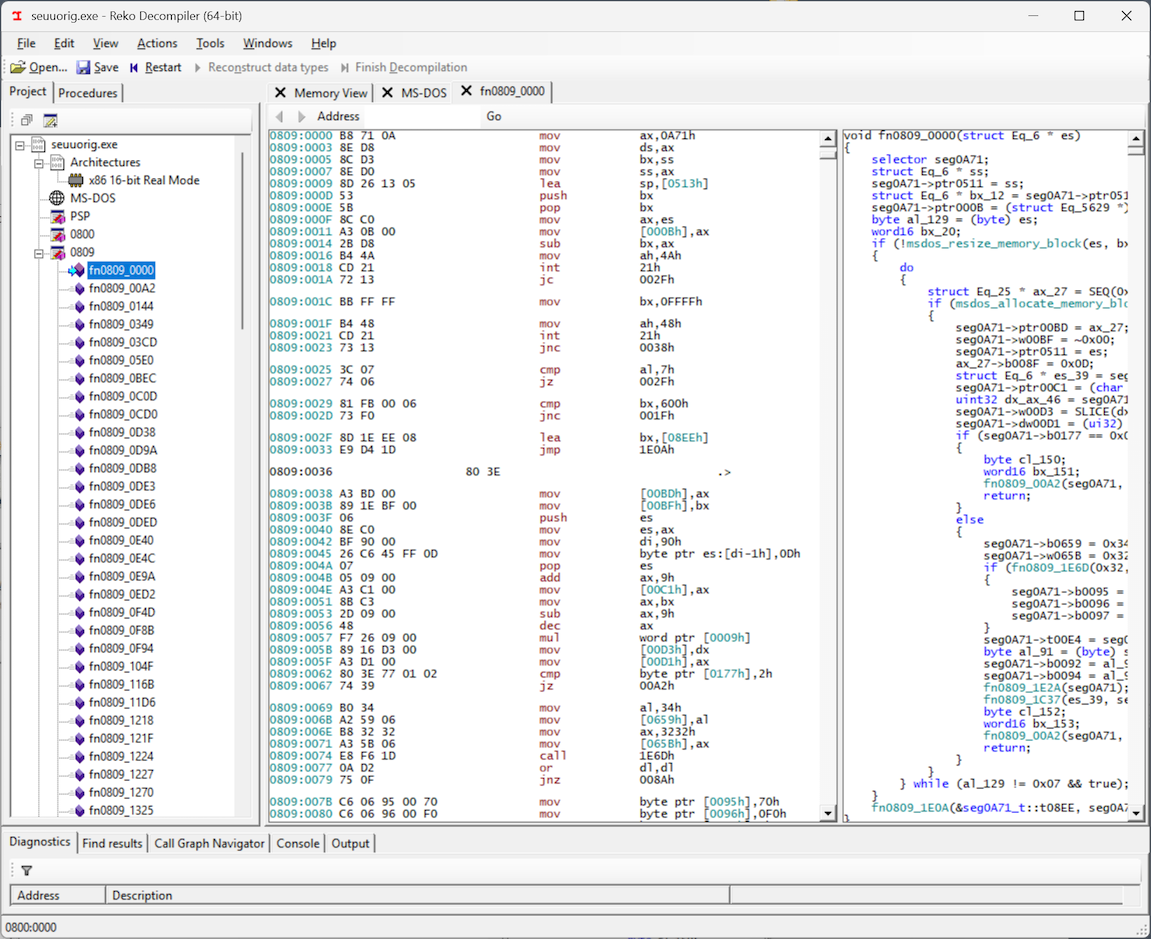

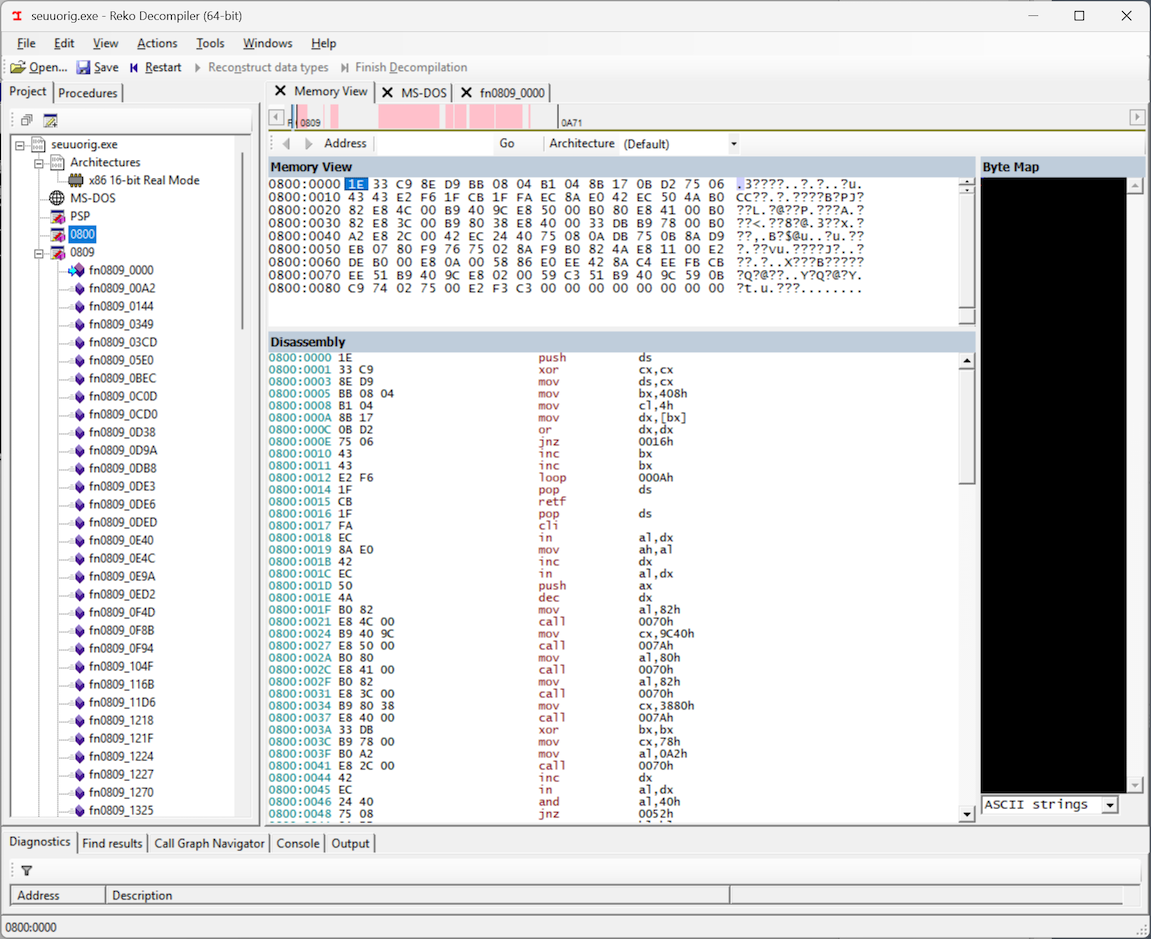

A great tool for disassembling executables of this vintage is Reko. It understands 16-bit real mode executables, and even attempts to decompile them into readable C code that corresponds to the disassembly.

And so, looking at the decompiled/disassembled code in Reko, I expected to find in and out instructions, which would be the telltale sign of the program trying to communicate with the parallel port through the PC’s I/O ports. However… I didn’t see an in or out instruction anywhere! But then I noticed something: Reko disassembled the executable into two “segments”: 0800 and 0809, and I was only looking at segment 0809.

If we look at segment 0800, we see the smoking gun: in and out instructions, meaning that the copy-protection routine is definitely here, and best of all, the entire code segment is a mere 0x90 bytes, which suggests that the entire routine should be pretty easy to unravel and understand. For some reason, Reko was not able to decompile this code into a C representation, but it still produced a disassembly, which will work just fine for our purposes. Maybe this was a primitive form of obfuscation from those early days, which is now confusing Reko and preventing it from associating this chunk of code with the rest of the program… who knows.

Here is a GitHub Gist with the disassembly of this code, along with my annotations and notes. My x86 assembly knowledge is a little rusty, but here is the gist of what this code does:

- It’s definitely a single self-contained routine, intended to be called using a “far”

CALLinstruction, since it returns with aRETFinstruction. - It begins by detecting the address of the parallel port, by reading the BIOS data area. If the computer has more than one parallel port, the dongle must be connected to the first parallel port (LPT1).

- It performs a loop where it writes values to the data register of the parallel port, and then reads the status register, and accumulates responses in the

BHandBLregisters. - At the end of the routine, the “result” of the whole procedure is stored in the

BXregister (BHandBLtogether), which will presumably be “verified” by the caller of the routine. - Very importantly, there doesn’t seem to be any “input” into this routine. It doesn’t pop anything from the stack, nor does it care about any register values passed into it. Which can only mean that the result of this routine is completely constant! No matter what complicated back-and-forth it does with the dongle, the result of this routine should always be the same.

With the knowledge that this routine must exit with some magic value stored in BX, we can now patch the first few bytes of the routine to do just that! Not yet knowing which value to put in BX, let’s start with 1234:

BB 34 12 MOV BX, 1234h

CB RETF

Only the first four bytes need patching — set BX to our desired value, and get out of there. Running the patched executable with these new bytes still fails (expectedly) with the same message of “No dongle, no edit”, but it fails immediately, instead of after several seconds of talking to the parallel port. Progress!

Stepping through the disassembly more closely, we get another major clue: The only value that BH can be at the end of the routine is 76h. So, our total value for the magic number in BX must be of the form 76xx. In other words, only the BL value remains unknown:

BB __ 76 MOV BX, 76__h

CB RETF

Since BL is an 8-bit register, it can only have 256 possible values. And what do we do when we have 256 combinations to try? Brute force it! I whipped up a script that plugs a value into that particular byte (from 0 to 255) and programmatically launches the executable in DosBox, and observes the output. Lo and behold, it worked! The brute forcing didn’t take long at all, because the correct number turned out to be… 6. Meaning that the total magic number in BX should be 7606h:

BB 06 76 MOV BX, 7606h

CB RETF

Bingo!

And then, proceeding to examine the other executable files in the compiler suite, the parallel port routine turns out to be exactly the same. All of the executables have the exact same copy protection logic, as if it was rubber-stamped onto them. In fact, when the compiler (RPGC.EXE) compiles some RPG source code, it seems to copy the parallel port routine from itself into the compiled program. That’s right: the patched version of the compiler will produce executables with the same patched copy protection routine! Very convenient.

I must say, this copy protection mechanism seems a bit… simplistic? A hardware dongle that just passes back a constant number? Defeatable with a four-byte patch? Is this really worthy of a patent? But who am I to pass judgment. It’s possible that I haven’t fully understood the logic, and the copy protection will somehow re-surface in another way. It’s also possible that the creators of the RPG compiler (Software West, Inc) didn’t take proper advantage of the hardware dongle, and used it in a way that is so easily bypassed.

In any case, Software West’s RPG II compiler is now free from the constraint of the parallel port dongle! And at some point soon, I’ll work on purging any PII from the compiler directories, and make this compiler available as an artifact of computing history. It doesn’t seem to be available anywhere else on the web. If anyone reading this was associated with Software West Inc, feel free to get in touch — I have many questions!

Microsoft's PowerToys team is contemplating building a top menu bar for Windows 11, much like Linux, macOS, or older versions of Windows. The menu bar, or Command Palette Dock as Microsoft calls it, would be a new optional UI that provides quick access to tools, monitoring of system resources, and much more.

Microsoft has provided concept images of what it's looking to build, and is soliciting feedback on whether Windows users would use a PowerToy like this. "The dock is designed to be highly configurable," explains Niels Laute, a senior product manager at Microsoft. "It can be positioned on the top, left, right, or bottom edge of the scree …

Memory usage can be hard to keep under control in Python projects.

The language doesn’t make it explicit where memory is allocated, module imports can have signficant costs, and it’s all too easy to create a global data structure that accidentally grows unbounded, leaking memory.

Django projects can be particularly susceptible to memory bloat, as they may import many large dependencies like numpy, even if they’re only used in a few places.

One tool to help understand your program’s memory usage is Memray, a memory profiler for Python created by developers at Bloomberg. Memray tracks where memory is allocated and deallocated during program execution. It can then present that data in various ways, including spectucular flame graphs, collapsing many stack traces into a chart where bar width represents memory allocation size.

Profile a Django project

Memray can profile any Python command with its memray run command.

For a Django project, I suggest you start by profiling the check management command, which loads your project and then runs system checks.

This is a good approximation of the minimum work required to start up your Django app, imposed on every server load and management command execution.

To profile check, run:

$ memray run manage.py check

Writing profile results into memray-manage.py.4579.bin

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

[memray] Successfully generated profile results.

You can now generate reports from the stored allocation records.

Some example commands to generate reports:

/.../.venv/bin/python3 -m memray flamegraph memray-manage.py.4579.bin

The command completes as normal, outputting System check identified no issues (0 silenced)..

Around that, Memray outputs information about its profiling, saved in a .bin file featuring the process ID, and a suggestion to follow up by generating a flame graph.

The flame graph is great, so go ahead and make it:

$ memray flamegraph memray-manage.py.4579.bin

Wrote memray-flamegraph-manage.py.4579.html

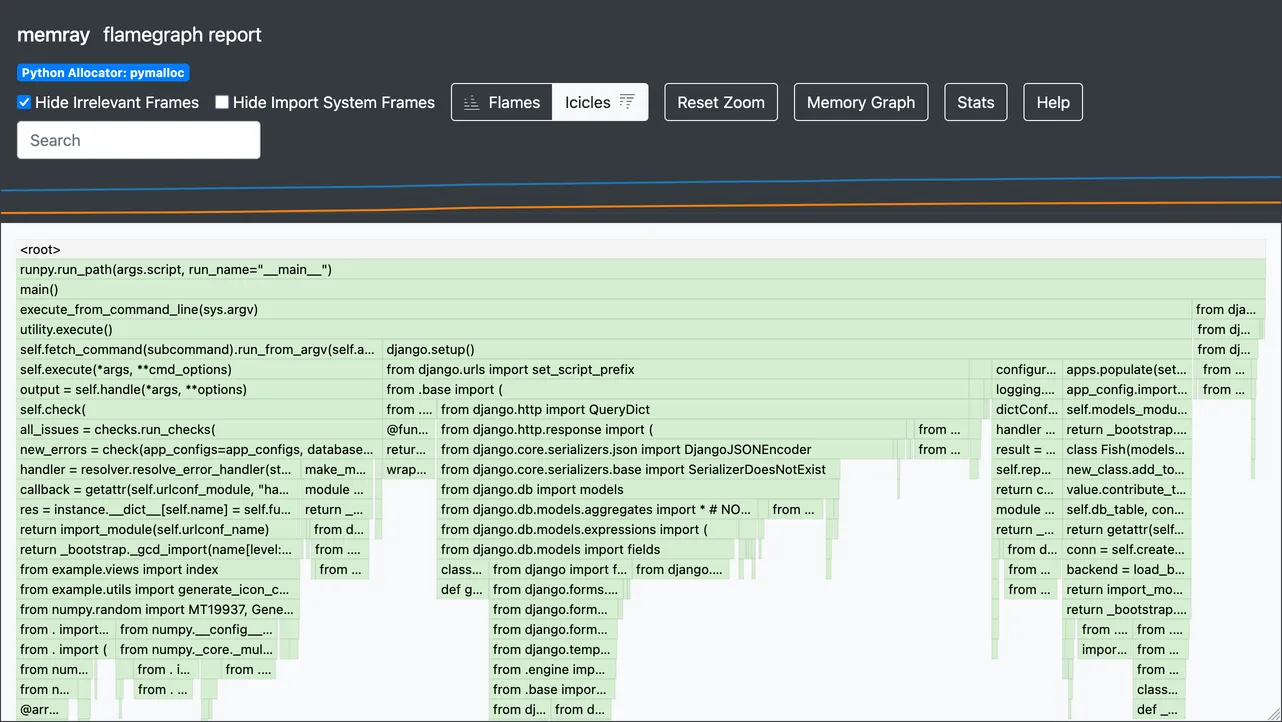

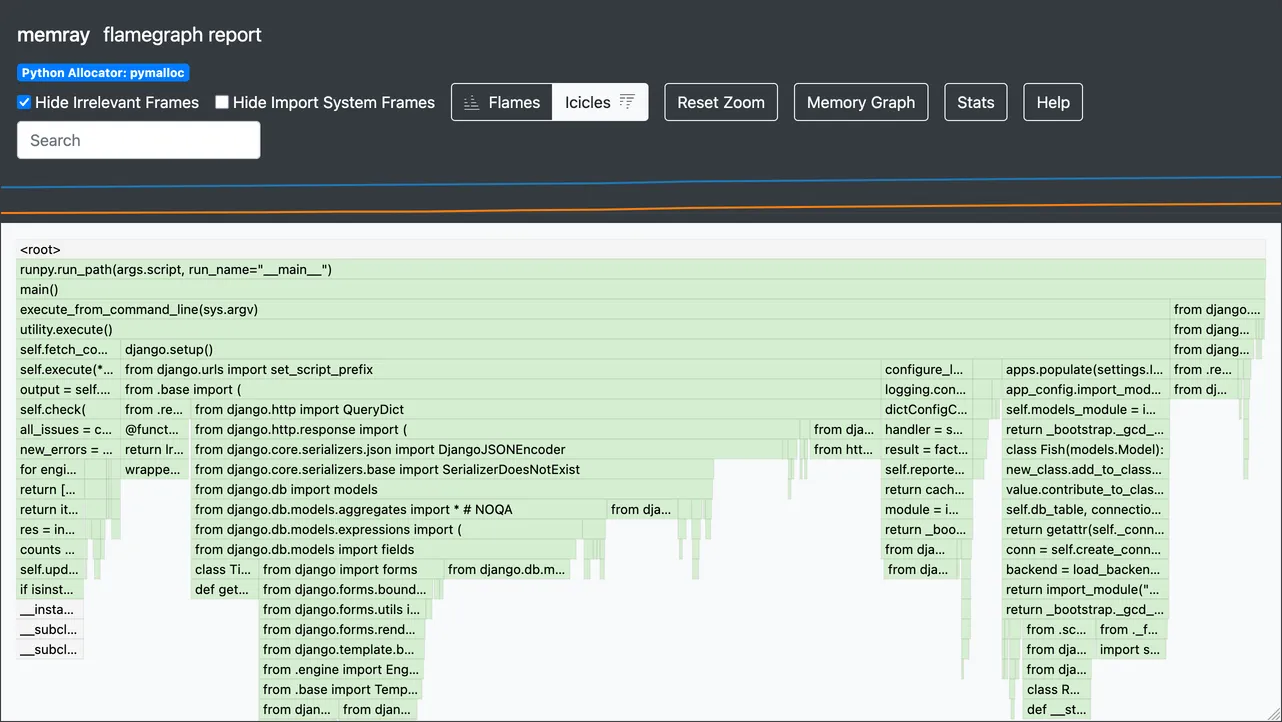

The result is a .html file you can open in your browser, which will look something like this:

The header of the page contains some controls, along with a mini graph tracking resident and heap memory over time. Underneath it is the main flame graph, showing memory allocations over time.

By default, the graph is actually an “icicle” graph, with frames stacked downward like icicles, rather than upward like flames. This matches Python’s stack trace representation, where the most recent call is at the bottom. Toggle between flame and icicle views with the buttons in the header.

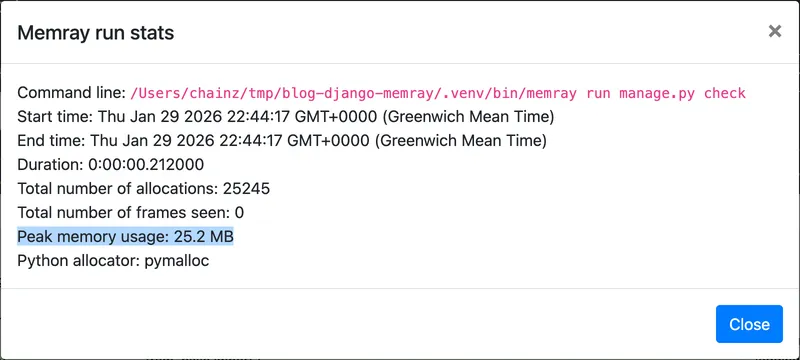

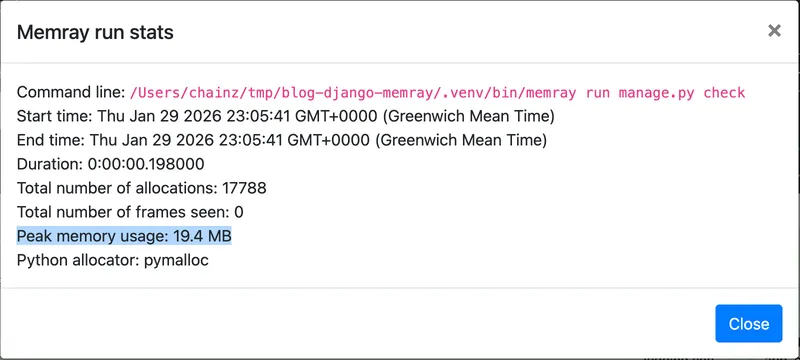

The Stats button at the top opens a dialog with several details, including the peak memory usage:

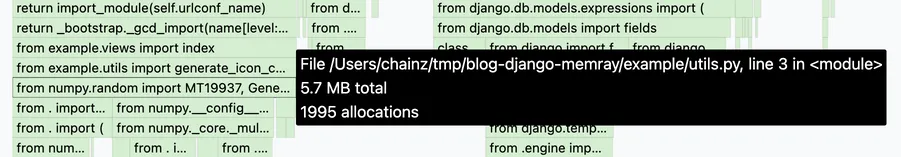

Frames in the graph display the line of code running at the time, and their width is proportional to the amount of memory allocated at that point. Hover a frame to reveal its details: filename, line number, memory allocated, and number of allocations:

Make an improvement

In the above example, I already narrowed in on a potential issue.

The line from numpy.random import ... allocates 5.7 MB of memory, about 23% of the peak usage of 25.2 MB.

This import occurs in example/utils.py, on line 3.

Let’s look at that code now:

from colorsys import hls_to_rgb

from numpy.random import MT19937, Generator

def generate_icon_colours(number: int) -> list[str]:

"""

Generate a list of distinct colours for the given number of icons.

"""

colours = []

for i in range(number):

hue = i / number

lightness = 0.5

saturation = 0.7

rgb = hls_to_rgb(hue, lightness, saturation)

hex_colour = "#" + "".join(f"{int(c * 255):02x}" for c in rgb)

colours.append(hex_colour)

Generator(MT19937(42)).shuffle(colours)

return colours

The code uses the Generator.shuffle() method from numpy.random to shuffle a list of generated colours.

Since importing numpy is costly, and this colour generation is only used in a few code paths (imagine we’d checked), we have a few options:

Delete the code—this is always an option if the function isn’t used or can be replaced with something simpler, like pregenerated lists of colours.

Defer the import until needed, by moving it within the function:

def generate_icon_colours(number: int) -> list[str]: """ Generate a list of distinct colours for the given number of icons. """ from numpy.random import MT19937, Generator ...

Doing so will avoid the import cost until the first time the function is called, or something else imports

numpy.random.Use a lazy import:

lazy from numpy.random import MT19937, Generator def generate_icon_colours(number: int) -> list[str]: ...

This syntax should become available from Python 3.15 (expected October 2026), following the implementation of PEP 810. It makes a given imported module or name only get imported on first usage.

Until it’s out, an alternative is available in

wrapt.lazy_import(), which creates an import-on-use module proxy:from wrapt import lazy_import npr = lazy_import("numpy.random") def generate_icon_colours(number: int) -> list[str]: ... npr.Generator(npr.MT19937(42)).shuffle(colours) ...

Use a lighter-weight alternative, for example Python’s built-in

random.shuffle()function:import random ... def generate_icon_colours(number: int) -> list[str]: ... random.shuffle(colours) ...

In this case, I would go with option 4, as it avoids the heavy numpy dependency altogether, will provide almost equivalent results, and doesn’t need any negotiation about changing functionality.

We will see an improvement in startup memory usage as long as no other startup code path also imports numpy.random.

After making an edit, re-profile and look for changes:

In this case, it seems the change worked and memory usage has reduced.

The flame graph looks like the right ~75% of the previous one, with “icicles” for regular parts of Django’s startup process, such as importing django.db.models and running configure_logging().

And the Stats dialog shows a lower peak value.

A drop from 25.2 MB to 19.4 MB, or 22% overall reduction!

(If the change hadn’t worked, we would probably have revealed another module that is loaded at startup and imports numpy.random.

Removing or deferring that import could then yield the saving.)

A Zsh one-liner to speed up checking results

If you use Zsh, you chain memray run, memray flamegraph, and opening the HTML result file with:

$ memray run manage.py check && memray flamegraph memray-*.bin(om[1]) && open -a Firefox memray-flamegraph-*.html(om[1])

This can really speed up doing multiple iterations measuring potential improvements.

I covered the (om[1]) globbing syntax in this previous Zsh-specific post.