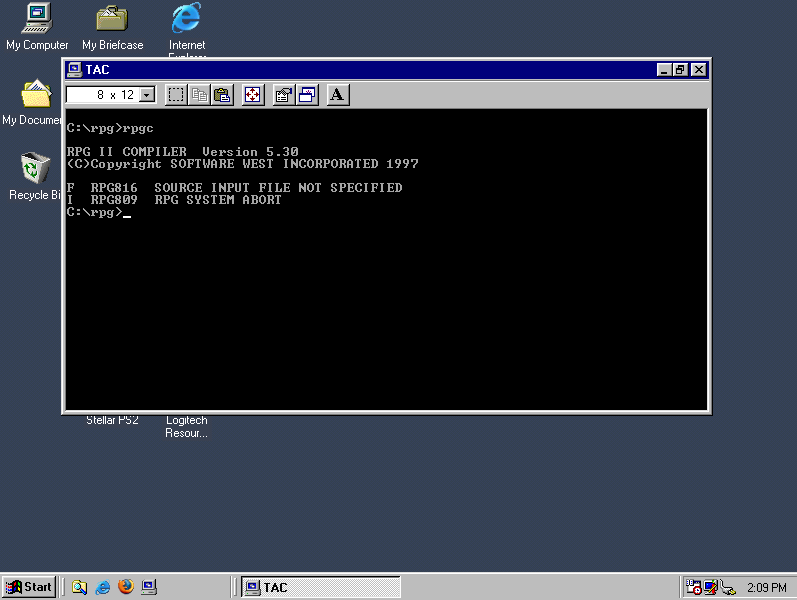

Over the past few months it's become clear that coding agents are extraordinarily good at building a weird version of a "clean room" implementation of code.

The most famous version of this pattern is when Compaq created a clean-room clone of the IBM BIOS back in 1982. They had one team of engineers reverse engineer the BIOS to create a specification, then handed that specification to another team to build a new ground-up version.

This process used to take multiple teams of engineers weeks or months to complete. Coding agents can do a version of this in hours - I experimented with a variant of this pattern against JustHTML back in December.

There are a lot of open questions about this, both ethically and legally. These appear to be coming to a head in the venerable chardet Python library.

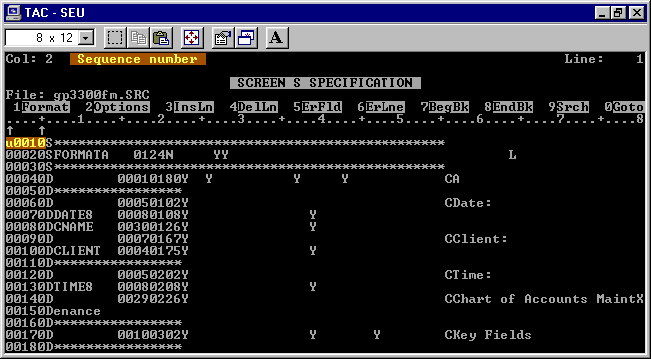

chardet was created by Mark Pilgrim back in 2006 and released under the LGPL. Mark retired from public internet life in 2011 and chardet's maintenance was taken over by others, most notably Dan Blanchard who has been responsible for every release since 1.1 in July 2012.

Two days ago Dan released chardet 7.0.0 with the following note in the release notes:

Ground-up, MIT-licensed rewrite of chardet. Same package name, same public API — drop-in replacement for chardet 5.x/6.x. Just way faster and more accurate!

Yesterday Mark Pilgrim opened #327: No right to relicense this project:

[...] First off, I would like to thank the current maintainers and everyone who has contributed to and improved this project over the years. Truly a Free Software success story.

However, it has been brought to my attention that, in the release 7.0.0, the maintainers claim to have the right to "relicense" the project. They have no such right; doing so is an explicit violation of the LGPL. Licensed code, when modified, must be released under the same LGPL license. Their claim that it is a "complete rewrite" is irrelevant, since they had ample exposure to the originally licensed code (i.e. this is not a "clean room" implementation). Adding a fancy code generator into the mix does not somehow grant them any additional rights.

Dan's lengthy reply included:

You're right that I have had extensive exposure to the original codebase: I've been maintaining it for over a decade. A traditional clean-room approach involves a strict separation between people with knowledge of the original and people writing the new implementation, and that separation did not exist here.

However, the purpose of clean-room methodology is to ensure the resulting code is not a derivative work of the original. It is a means to an end, not the end itself. In this case, I can demonstrate that the end result is the same — the new code is structurally independent of the old code — through direct measurement rather than process guarantees alone.

Dan goes on to present results from the JPlag tool - which describes itself as "State-of-the-Art Source Code Plagiarism & Collusion Detection" - showing that the new 7.0.0 release has a max similarity of 1.29% with the previous release and 0.64% with the 1.1 version. Other release versions had similarities more in the 80-93% range.

He then shares critical details about his process, highlights mine:

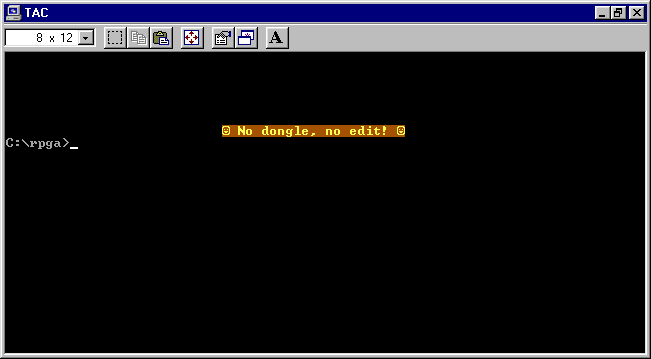

For full transparency, here's how the rewrite was conducted. I used the superpowers brainstorming skill to create a design document specifying the architecture and approach I wanted based on the following requirements I had for the rewrite [...]

I then started in an empty repository with no access to the old source tree, and explicitly instructed Claude not to base anything on LGPL/GPL-licensed code. I then reviewed, tested, and iterated on every piece of the result using Claude. [...]

I understand this is a new and uncomfortable area, and that using AI tools in the rewrite of a long-standing open source project raises legitimate questions. But the evidence here is clear: 7.0 is an independent work, not a derivative of the LGPL-licensed codebase. The MIT license applies to it legitimately.

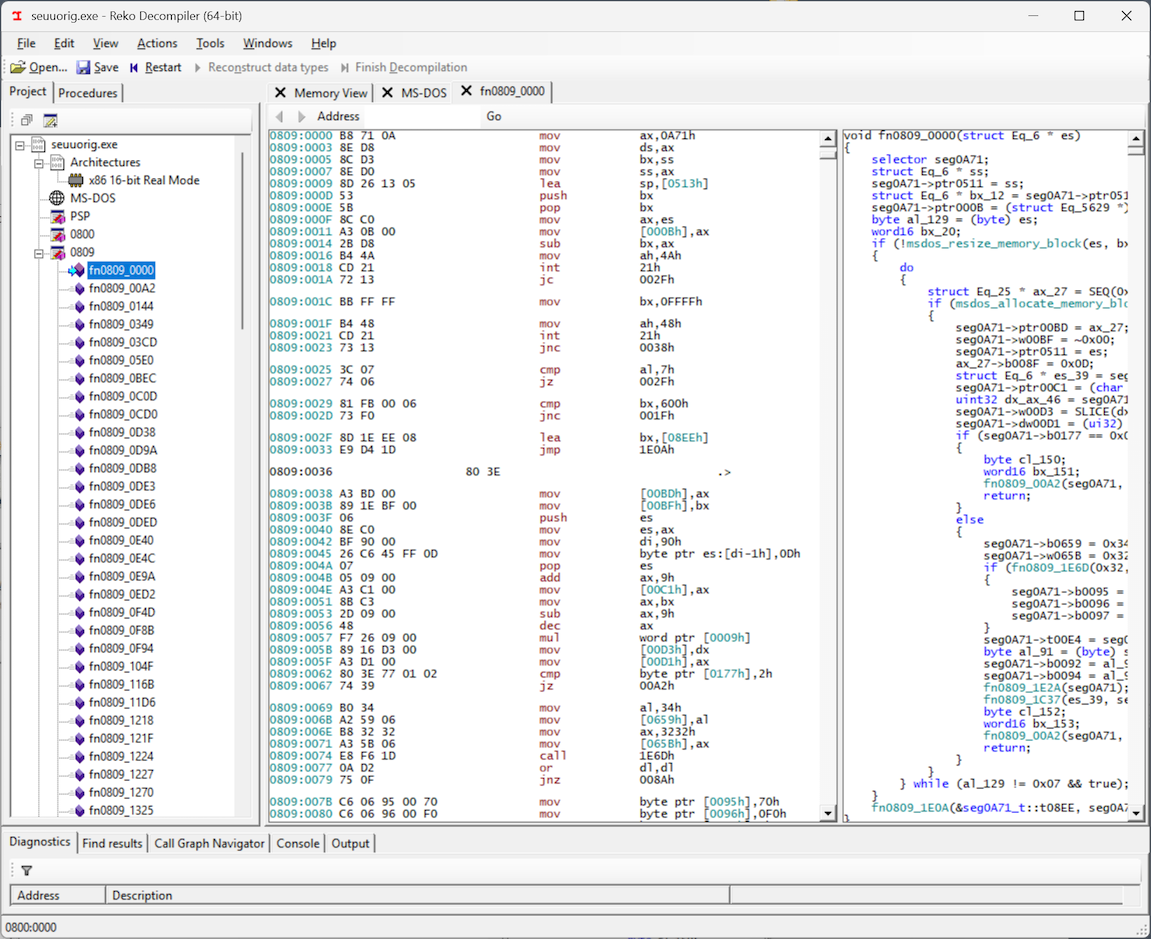

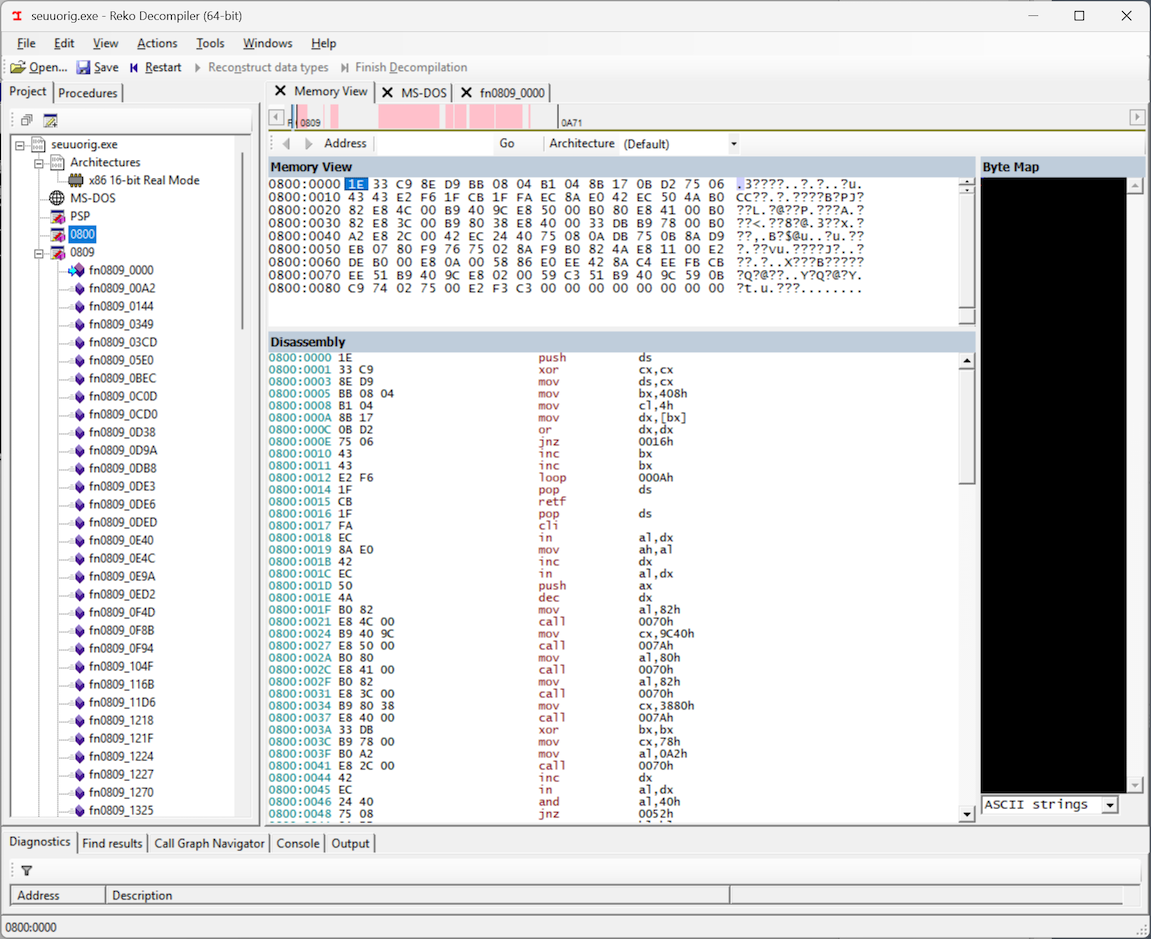

Since the rewrite was conducted using Claude Code there are a whole lot of interesting artifacts available in the repo. 2026-02-25-chardet-rewrite-plan.md is particularly detailed, stepping through each stage of the rewrite process in turn - starting with the tests, then fleshing out the planned replacement code.

There are several twists that make this case particularly hard to confidently resolve:

- Dan has been immersed in chardet for over a decade, and has clearly been strongly influenced by the original codebase.

- There is one example where Claude Code referenced parts of the codebase while it worked, as shown in the plan - it looked at metadata/charsets.py, a file that lists charsets and their properties expressed as a dictionary of dataclasses.

- More complicated: Claude itself was very likely trained on chardet as part of its enormous quantity of training data - though we have no way of confirming this for sure. Can a model trained on a codebase produce a morally or legally defensible clean-room implementation?

- As discussed in this issue from 2014 (where Dan first openly contemplated a license change) Mark Pilgrim's original code was a manual port from C to Python of Mozilla's MPL-licensed character detection library.

- How significant is the fact that the new release of chardet used the same PyPI package name as the old one? Would a fresh release under a new name have been more defensible?

I have no idea how this one is going to play out. I'm personally leaning towards the idea that the rewrite is legitimate, but the arguments on both sides of this are entirely credible.

I see this as a microcosm of the larger question around coding agents for fresh implementations of existing, mature code. This question is hitting the open source world first, but I expect it will soon start showing up in Compaq-like scenarios in the commercial world.

Once commercial companies see that their closely held IP is under threat I expect we'll see some well-funded litigation.

Update 6th March 2026: A detail that's worth emphasizing is that Dan does not claim that the new implementation is a pure "clean room" rewrite. Quoting his comment again:

A traditional clean-room approach involves a strict separation between people with knowledge of the original and people writing the new implementation, and that separation did not exist here.

I can't find it now, but I saw a comment somewhere that pointed out the absurdity of Dan being blocked from working on a new implementation of character detection as a result of the volunteer effort he put into helping to maintain an existing open source library in that domain.

I enjoyed Armin's take on this situation in AI And The Ship of Theseus, in particular:

There are huge consequences to this. When the cost of generating code goes down that much, and we can re-implement it from test suites alone, what does that mean for the future of software? Will we see a lot of software re-emerging under more permissive licenses? Will we see a lot of proprietary software re-emerging as open source? Will we see a lot of software re-emerging as proprietary?

Tags: licensing, mark-pilgrim, open-source, ai, generative-ai, llms, ai-assisted-programming, ai-ethics, coding-agents